Exploring the question of existence – the nature of being, “where” we come from and why – is a recurring sticking point between the worlds of faith and science. Ironically, it’s also the uniting ideological thread between the two: the idea that, with enough dedication and the right perspective, humans can understand the origin of life. For some scientists who see it, like astrophysicist Dr. Anton Koekemoer, the harmony between faith and science couldn’t be more apparent; for others, it remains largely speculative.

Naturally, this facet of human existence is probed in the pages of The Saint John’s Bible, which incorporates modern understandings of our place in the universe and illuminations that allude to the unknowability of the beginning. The Saint John’s Bible Heritage Edition have been used in academic contexts around the world, including in Dr. Gintaras Duda’s courses.

“I always make it a point of bringing [students] over to the rare books room just to see [the Heritage Edition], just because it had such a big impact on me,” he said. Duda is a professor of physics at Creighton University researching dark matter. He’s also one of the university’s leading voices on the intersection of science and religion. “I think it’s just this great sort of living demonstration of exactly what the Catholic intellectual tradition really is.”

Duda has been intentional about using The Saint John’s Bible in his courses. “I really want my students to have their minds both theologically and scientifically in the 21st century. [At Creighton University] we don’t expect students to be Catholic or to buy any particular religion, but dang it we want you to think about it, right? So we want you to confront these kinds of truths and at least ponder them and think about that.”

A Passion for Science and a Faith Dedication Collide

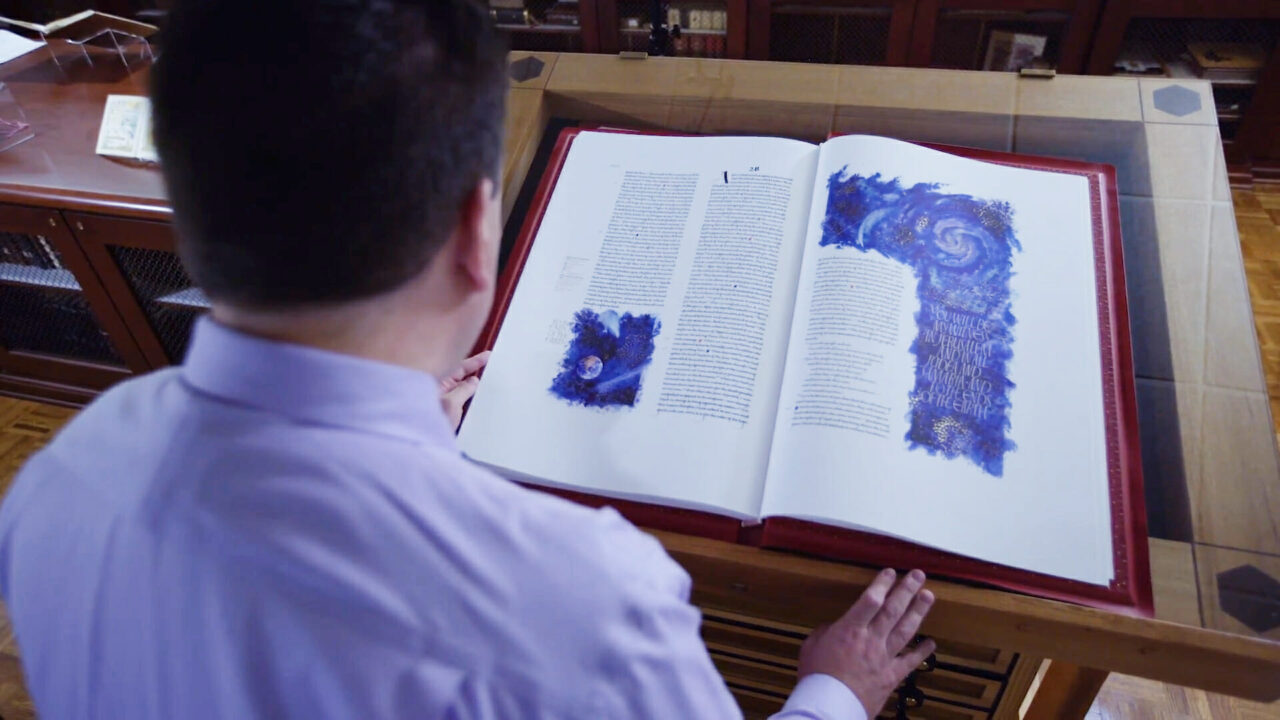

Duda said the concept of faith meeting science rather than combating it is highlighted in To the Ends of the Earth, an iconic illumination from the Gospels and Acts volume of The Saint John’s Bible.

“That one really spoke to me,” he said. There’re certain moments in your life where you don’t forget, and I remember being a high school junior sitting in the back of my parents’ car reading a little book on general relativity and this sort of notion that curvature was actually gravity and gravity is curvature and that the geometry of space-time is related to gravity.

“It was such a mind-blowing moment. And then to see that illumination and just see the sort of geometric patterns … you’re talking about mathematics and sort of that structure of the universe. To see that in a religious text was almost overwhelming. Here’s living proof right in front of you that there doesn’t have to be a conflict between science and religion. These two things can be both celebrated in the same place at the same time.”

For Dr. Sarah Yost, associate professor at the College of Saint Benedict and Saint John’s University who focuses on gamma ray bursts, the connection between intrinsic faith and human curiosity isn’t just frictionless, but complementary: “The physics, chemistry, biology and so on is the ‘what,’ and religion is ‘why,”’ she says. “Why is there anything? What’s the meaning of all of that? I don’t need to require a God of the gaps or anything like that to believe in God. I actually much prefer the concept of a very much more personally involved God who occasionally produces miracles.

“I never saw science as trying to exclude God, even though there are scientists who attempt to do so,” she continued. “It’s like that old joke about the scientist saying that he doesn’t need God. God says to the scientist, ‘Let’s compete and see who can produce a tree.’ And so the scientist says, ‘Well, I’ll just go and gene sequence that – I’ll start building it from atoms.’

“‘Stop, stop, stop,’ says God. ‘Go make your own atoms.’”

Unique Perspectives Unified by a Single Artistic Message

There’s something humbling about the way scientists like Duda and Yost talk about The Saint John’s Bible –despite their extensive knowledge about nearly inscrutable topics, their interpretations of the art and message of The Saint John’s Bible are as subjective as anyone’s. Dr. Yost also mentioned To the Ends of the Earth in discussing her impression of its illuminations.

“[T]here is the idea in Catholic theology about the ‘Book of Nature,” which states that nature should reveal to us things about God. So I thought [the art of The Saint John’s Bible] was very nice to tie in … When it comes to astronomy, we’re perhaps the more lucky branch of physics in that we often [generate] some very pretty pictures. We get these very striking images that we learn from and the public can see the awe-inspiring beauty of it, which I think very much connects with our sense of the divine behind creation.”

“There’s the binary code, there’s equation, there are planetary orbits…” Duda’s eye lingers on the elements of science and mathematics in Fulfillment of Creation, an illumination from Volume 7. “At the beginning of Ecclesiastes, there’s this beautiful illumination which – I don’t know if it’s quite intended, but it almost looks to me just like there’s kind of a swirl of galaxies. So there’s astronomy and cosmology just kind of throughout the whole Saint John’s Bible. It’s not just in one spot, it’s kind of everywhere.”

The Mystery of What We’re Missing “Draws People In”

Duda and Yost’s areas of professional focus may differ, but there is one area they share an interest in: probing the limits of human observation to determine what’s on the other side of the unknown. Duda said that no matter what advancements are made, religion and science will always “inform each other” in our understanding of existence.

“If theology is going to inform how we do science, how we live and how scientists think about things,” he said, “then certainly [it] should be the other way around, right? Science should inform theology as well.”

“I think dark matter and dark energy are these really, really interesting puzzles, these kinds of mysteries,” Duda said. “[W]e discovered that there’s all this sort of mass out there that you can effectively “see” through gravity and you know it’s there, and there are so many lines of evidence that point to it there, but we don’t have a really good fundamental understanding of what the heck could it be. I think it’s that mysteriousness that draws people in … I think that verges very much on a kind of religious question.”

Yost went even further, noting how physicists working to develop a Theory of Everything could drastically alter the way humans see the world and themselves. “It’s honestly a theory of absolutely everything, about understanding how that connects,” she said, since theories of very small scales and large gravitational effects do not yet work together.

“There might be stuff that we are missing. And I don’t know exactly what that might reveal about the universe, but it could be something very deep.”

“One thing that made me a scientist was being passionate about truth, about finding things out, about uncovering things,” she said. “I don’t think you can do theology or have faith without that, either. You have to have a passion for truth on the theological side as well, right? Those two sides are so mutually complementary. The same skills that make you a good scientist can help you achieve this deep and very meaningful faith.”